Promoting Physical Activity with Temporary Street Closures

By: Keshia Pollack Porter, PhD, MPH, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Renée Umstattd Meyer, PhD, MCHES, Baylor University, and Amanda Walker, MSRS, Physical Activity Research Center

[Reprinted with permission from Parks & Recreation magazine from its May 2018 issue. Copyright 2018 by the National Recreation and Park Association. Also available online here.]

Parks and playgrounds are a good source of physical activity for kids, but not all kids have access to safe and well-maintained facilities. In fact, lower-income communities and communities of color tend to have less access to quality park and recreation facilities. Research shows that Latinos, African-Americans and lower-income individuals are more likely to live in areas that have fewer park acres per person compared to whites and individuals in higher-income communities. Traffic and crime are also barriers to safe outdoor play and activity in some communities.

The concept of “Play Streets” has emerged as a way to promote outdoor play and physical activity for children in neighborhoods without access to safe, well-maintained parks and playgrounds. Play Streets are temporary street closures that, for a specified time, create safe play spaces. These closures can be recurring or episodic and offer a safe place for children to be physically active without traffic-safety concerns. Banning vehicles from the streets also has the added benefit of improving air quality, as well as enhancing neighborhoods by building partnerships and increasing social cohesion. Thus, Play Streets not only provide places for safe play, but also advance health equity. Play Streets have primarily been implemented in urban areas, so there is a lack of examples and resources for rural communities to use.

Play Streets Case Study

With support from the Physical Activity Research Center (PARC), we selected four rural communities — in Maryland, North Carolina, Oklahoma and Texas — each with a history of hosting community events, to organize and host Play Streets during summer 2017. PARC is a collaboration of internationally recognized faculty from five leading universities — University of California – San Diego, Georgia Institute of Technology, North Carolina State University, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Baylor University — with backgrounds in public health, city planning, behavioral science, and parks and recreation. It is funded by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation as part of a larger effort to build an inclusive Culture of Health across America to ensure that all children have opportunities to grow up at a healthy weight.

The communities received mini-grants to use to purchase equipment for free play, rent equipment and purchase snacks (we encouraged healthy snacks) for four Play Streets during the summer months. We studied how each community implemented the Play Streets, including how they were advertised, available activities and when they were held. We used a popular and valid tool for observing physical activity, called SOPARC (System for Observing Play and Recreation in Communities), and pedometers to measure how active kids and adults were at the Play Streets. We also completed a systematic review of the peer-reviewed and “grey” literature to document what we know about Play Streets and their impacts on play for children, physical activity levels and communities.

The literature review evaluated hundreds of documents, and, based on 13 peer-reviewed articles and 36 reports/documents that met our inclusion criteria, we found the following:

- Play Streets have mainly been implemented in cities and suburban areas.

- Play Streets were described as safe places for children to play because of reduced traffic and increased supervision.

- Only a few studies measured physical activity as an outcome.

- Play Streets strengthen communities and increase social interactions.

- Some residents complained about traffic detours and noise on the days that Play Streets were held.

- Some organizations that hosted Play Streets hope they can decrease crime and violence among adolescents.

Preliminary Findings

While we are still in the early stages of analyzing the data from the four communities, our preliminary findings are that Play Streets are a good way to get kids active in rural communities. Each of the Play Streets included a variety of activities using temporary play spaces and equipment, with inflatables being the most popular activity and where children seemed to be most active. We also found that in rural communities, streets are not always the most accessible places for Play Streets to be implemented, considering that there are fewer streets and those streets often are major thoroughfares through town (hence, they cannot be closed to traffic!).

Play Streets in rural areas might actually be more accessible in other public spaces, like fields and/or parking lots. For instance, one community collaborated with its local park and recreation department to identify a location for the Play Streets, which ended up occurring on sections of an underutilized public park, including the parking lot.

We are also learning how each community implemented Play Streets, including the partners they are working with and how limited resources are being creatively combined within these organizations. For example, one community partnered with a summer meals program and hosted the Play Streets at a time that overlapped with when children were picked up for their summer meal. The intentional “coupling” of Play Streets with other community or organization events was consistent across the four communities. This approach allowed organizations not only to capitalize on shared resources, but also to reduce the burden and barrier of suburban sprawl faced by rural residents, who often had to travel via car to attend the Play Streets. We look forward to learning more about the impacts of Play Streets on children and families, in addition to important lessons regarding how communities should organize and run them.

Conclusion

For individuals interested in this method of intervention to promote outdoor play, it is important to know that Play Streets offer an opportunity for safe outdoor play for children, especially in communities that lack safe parks and playgrounds, and/or available and affordable programming opportunities. They are relatively low cost and carry many potential benefits for host organizations, the children who participate and the broader community. Play Streets are a promising intervention strategy that can help communities close gaps in availability of and access to safe places to play and enhance health equity while doing so, especially in areas that have fewer resources and greater challenges to supporting and promoting physical activity and play.

The practicality and low costs of Play Streets also provide a “reachable” solution to address challenges around access and availability of safe play spaces that can simultaneously bring communities together in a meaningful manner not only to support their children, but also to improve community connectedness and capacity, potentially increasing social networks within the community and collective efficacy. In many rural areas, public resources are limited, and the idea of advocating for new parks or even renovating parks or other play areas can be daunting and often unrealistic as an immediate or even long-term solution. Working with communities to understand how to advocate for some of these larger environmental changes remains important; however, Play Streets offer a more attainable, immediate and likely sustainable solution, with potential for broader social impacts and reach.

Keshia Pollack Porter is a Professor at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. M. Renée Umstattd Meyer is an Associate Professor of Public Health at Baylor University. Amanda Walker is a Research Associate for Active Living Research and the Physical Activity Research Center at the University of California San Diego.

The main reason schools make PA a priority is because PA helps advance learning and health goals. The study participants mentioned they know from research and from direct experience (e.g., as teachers, principals) that PA can yield multiple learning-related benefits, including better focus in class and improved test scores. Additionally, PA is seen as a strategy to help reduce obesity and inactivity, improve physical, mental and behavioral health, and social and emotional learning. One respondent shared “You got to exercise their brains!”

The main reason schools make PA a priority is because PA helps advance learning and health goals. The study participants mentioned they know from research and from direct experience (e.g., as teachers, principals) that PA can yield multiple learning-related benefits, including better focus in class and improved test scores. Additionally, PA is seen as a strategy to help reduce obesity and inactivity, improve physical, mental and behavioral health, and social and emotional learning. One respondent shared “You got to exercise their brains!” In cities across the country, public parks and playgrounds provide opportunities to increase routine physical activity among children during non-school hours. Because neighborhood parks are widely available and affordable, their potential to encourage children to be more active is particularly important in low-income communities of color.

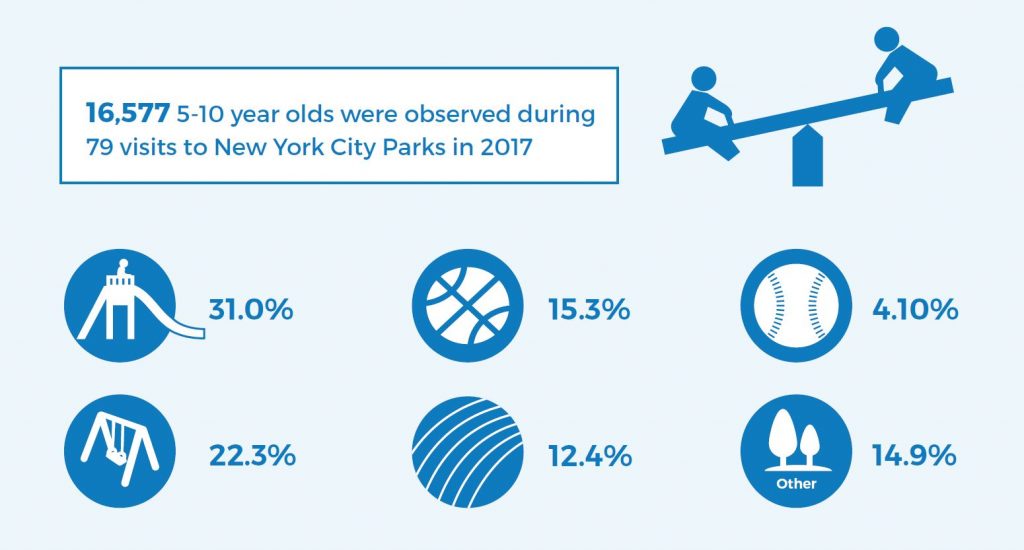

In cities across the country, public parks and playgrounds provide opportunities to increase routine physical activity among children during non-school hours. Because neighborhood parks are widely available and affordable, their potential to encourage children to be more active is particularly important in low-income communities of color.  As PARC focuses on kids between 5 and 10 years of age, we want to share our observations on observing children across all these days; 79 unique days in fact. Over 16,500 children were observed during this study. Each momentary scan averaged over 1.5 children per area observed, or 56 children observed per hour. Playgrounds had the most children and there were more in the parks from 6-7pm than any other time (10am, 3pm, 3:30pm). More children were observed in parks during the school year than the summer, and more on weekend observations than weekdays. Areas of the park where organized activities were occurring or were in the shade were more popular than those not organized or in full sun.

As PARC focuses on kids between 5 and 10 years of age, we want to share our observations on observing children across all these days; 79 unique days in fact. Over 16,500 children were observed during this study. Each momentary scan averaged over 1.5 children per area observed, or 56 children observed per hour. Playgrounds had the most children and there were more in the parks from 6-7pm than any other time (10am, 3pm, 3:30pm). More children were observed in parks during the school year than the summer, and more on weekend observations than weekdays. Areas of the park where organized activities were occurring or were in the shade were more popular than those not organized or in full sun. The parks and playgrounds we observed in New York City were well used. Across all visits, children were present over 60% of the momentary scans of playgrounds. Kids ran from playground area to swings to splash areas while parents, guardians, or older siblings sat nearby in the shade. During one observation, a parks staff member brought out bouncy balls, cones, and hula hoops, just setting these in the middle of the playground area. He did not provide instructions, but allowed the children to use the equipment as they wanted. A hula hoop competition ensued in one corner followed by the use of a hula hoop set on cones as a sort of basketball hoop with children running around and throwing the balls toward the hoops while others blocked their shots. Also anecdotally we saw families spending multiple hours in the parks during the summer, especially those parks featuring splash areas for the kids.

The parks and playgrounds we observed in New York City were well used. Across all visits, children were present over 60% of the momentary scans of playgrounds. Kids ran from playground area to swings to splash areas while parents, guardians, or older siblings sat nearby in the shade. During one observation, a parks staff member brought out bouncy balls, cones, and hula hoops, just setting these in the middle of the playground area. He did not provide instructions, but allowed the children to use the equipment as they wanted. A hula hoop competition ensued in one corner followed by the use of a hula hoop set on cones as a sort of basketball hoop with children running around and throwing the balls toward the hoops while others blocked their shots. Also anecdotally we saw families spending multiple hours in the parks during the summer, especially those parks featuring splash areas for the kids. In the highly dense environments of New York the space of a park and playground and even the simplest of play equipment kept the parks well used across the four months of observations.

In the highly dense environments of New York the space of a park and playground and even the simplest of play equipment kept the parks well used across the four months of observations.