Physical activity of school-age children at Play Streets in rural communities

By: M. Renée Umstattd Meyer, Christina N. Bridges Hamilton, Tyler Prochnow, Megan E. McClendon, Emily Wilkins, and Gabriel Benavidez from Baylor University; Tiffany D. Williams from Gramercy Group; Christiaan G. Abildso from West Virginia University; and Kimberly T. Arnold and Keshia M. Pollack Porter from Johns Hopkins University

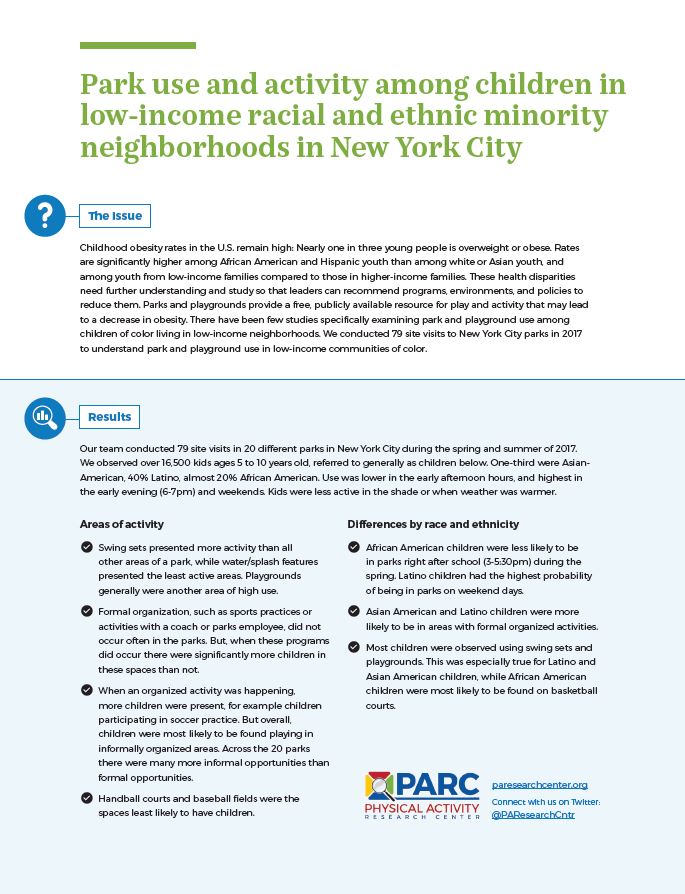

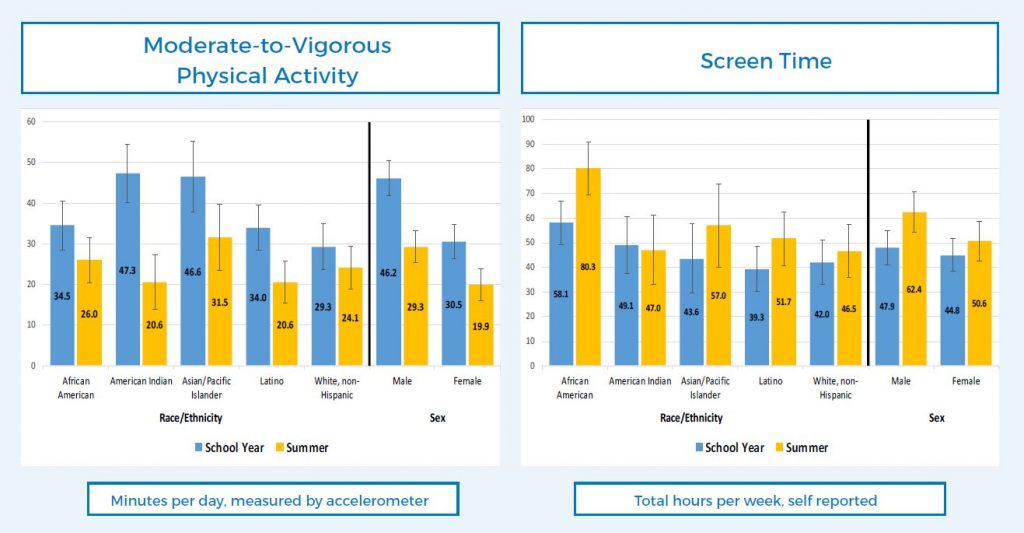

Child physical activity is important for many health outcomes, yet few children are active enough to realize these benefits. Children of color and those residing in low-income communities face even greater challenges to engaging in recommended levels of physical activity. Children play outside less than their parents did at the same age. Residents of rural communities may face obstacles to being active, including fewer parks, playgrounds, and programs and greater geographic dispersion.

Play Streets, temporary street closures that create safe places for children to play, could be an innovative solution to promote active play in rural communities. The purpose of this study was to examine physical activity of school-aged children during Play Streets that occurred in Summer 2017 in four low-income rural communities of different races and ethnicities.

Results

Perceptions and participant characteristics

- Most school-aged children who attended the Play Streets reported it was their first time.

- Children agreed or strongly agreed that their town has friendly (safe/attractive) places to walk and/or bike.

- Almost all children (96%) agreed or strongly agreed they felt safe at a Play Street.

- Over half of the children (59%) said they were physically active in their free time quite often (5-6 times last week) or very often (7 or more times last week) during the last week before the Play Street.

- Physical activity was described in this question as including sports or dance that make you sweat or make your legs feel tired, or games that make you breathe hard, like tag, skipping, running, climbing, and others.

Physical activity at Play Streets – Pedometer measured

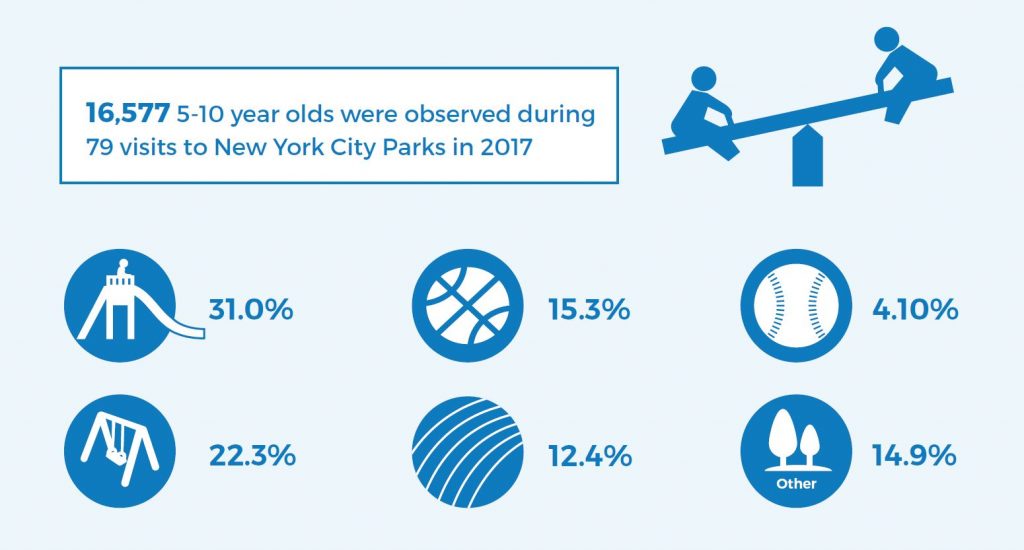

- A total of 372 elementary-to-middle school-aged children wore pedometers at the Play Streets to measure their physical activity, an average of 23 children at each Play Street. Children who wore pedometers were on average 9 years old and 55% were female.

- Children wore the pedometers for an average of 93 minutes, with 42 steps per minute or 3,906 steps overall, while wearing the pedometer.

- For context, existing studies show that children of varying ages accrue on average 918–1,943 total steps while in 15-29 minutes of recess.

- There were no statistically significant differences in steps per minute between boys and girls.

- When examining differences between boys and girls by age category, there were no significant differences between boys and girls for age groups other than 12-15 year-olds.

- Boys aged 12-15 years recorded significantly greater steps per minute than girls and wore the pedometers longer on average.

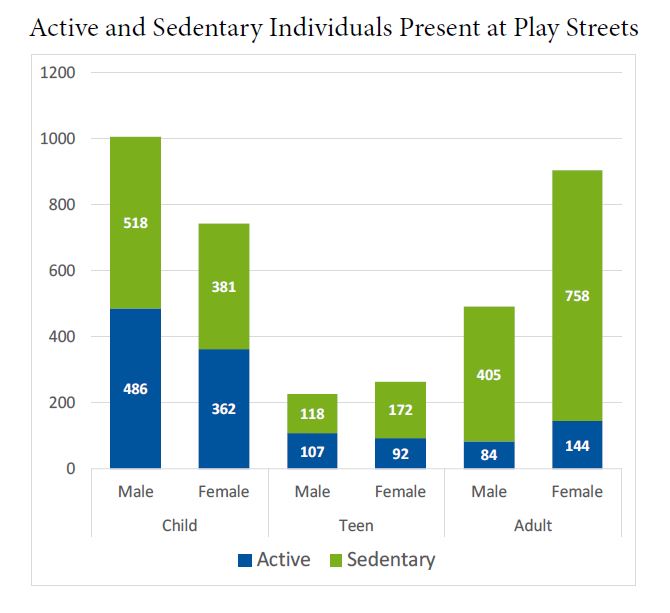

Physical activity at Play Streets – Systematic observation measured

- Roughly half of all children observed were physically active at the Play Street (49%).

- There was no significant difference in boys versus girls on physical activity except for male teens who were more likely to be physically active than female teens.

- Overall, children were also more likely to be physically active than teens.

- Areas containing inflatables (e.g., bounce houses, inflatable obstacle courses) had the highest percentage of physically active children.

- Male children were significantly more likely to bee observed in sport court and field activity areas than female children; although both males and females present in a sport court or field activity area were mostly active.

Findings from this lay summary are available in the full article, published in the Preventive Medicine:

Umstattd Meyer MR, Bridges Hamilton CN, Prochnow T, McClendon ME, Arnold KT, Wilkins E, et al. Come together, play, be active: Physical activity engagement of school-age children at Play Streets in four diverse rural communities in the U.S. Preventive Medicine. 2019, 129; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.105869.

Suggested Citation for Lay Summary:

Umstattd Meyer MR, Bridges Hamilton CN, et al. Physical activity of school-age children at Play Streets in rural communities. A Lay Summary. San Diego, CA: Physical Activity Research Center; Waco, TX: Baylor University; and Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2019. Available at: https://paresearchcenter.org/physical-activity-of-school-age-children-at-play-streets-in-rural-communities/.

This lay summary was made possible with funding from the Physical Activity Research Center. The research that generated the lay summary was led by Drs. Keshia M. Pollack Porter from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and M. Renée Umstattd Meyer from Baylor University.